Friday, December 18, 2020

Thursday, December 17, 2020

Saturday, December 12, 2020

Monday, November 16, 2020

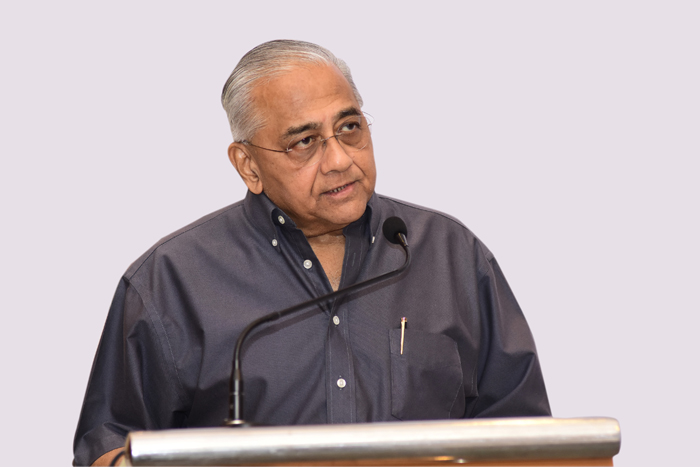

N Sankar, at 75

N. Sankar, at 75

V. RAMNARAYAN

If S. Muthiah was our founder, N. Sankar was our saviour. As Muthiah never tired of saying, had not Sankar stepped in at a crucial point in the life of Madras Musings and placed it on a sound financial footing with support from multiple corporate houses, the magazine would have been short lived. On the occasion of his 75th birthday, we wish our saviour and patron-in-chief many more years of good health and all happiness – The Editor

A true icon of Indian industry will turn 75 on November 19th. At the forefront of the Indian PVC manufacturing segment for over four decades, N. Sankar, the chairman of The Sanmar Group, presiding over a US $ one billion diversified multinational group, has been a role model for entrepreneurs and institution builders alike, characterised by an unusual combination of business acumen and ethical conviction – upright, farsighted, innovative. A pioneer in PVC manufacture, he was responsible for some of the most original choices made in the field including the highly integrated manufacturing processes at the numerous facilities of Chemplast, its flagship company, now over fifty years old.

Though the son and grandson of trailblazers in the history of south Indian industry and commerce – respectively K.S. Narayanan and S.N.N. Sankaralinga Iyer – Sankar was not born with a silver spoon, certainly not in a career sense. He obtained his B.Sc. (Tech) in Chemical Engineering from the AC College of Technology, Madras, graduating with distinction, and a Masters degree from the Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago. He joined Chemplast in 1967 to help his father. In an interview years ago for Rediff News by Shobha Warrier, he recalled, “I was born in an entrepreneurial family of three generations, so automatically I also became an entrepreneur. I had no funds of my own to start an enterprise at that time. From 1967 to 1972, I worked with Chemplast, reporting to S. Ramaswamy, the chief executive of the company. I learnt a lot from him in those five years. He taught me simple things from how to draft a letter to how to manage people. Those were the most difficult times for Chemplast. But I learnt to cope with it.”

In 1972, Sankar started his entrepreneurial career, borrowing from friends and investors to acquire a majority stake in a company called Industrial Chemicals and Monomers. Determined to bring in technology to India to manufacture products of excellence as a measure of import substitution, he, all of 26 years old, was writing letters to foreign companies seeking collaboration with them, something very nearly unheard of then.

In search of mechanical seals it needed, Chemplast zoomed in on Durametallic of Michigan as its choice. Durametallic India at Karapakkam. Madras, resulted, growing into what is now Sanmar Engineering Technolgies Private Limited, an engineering group within the Sanmar Group, catering to a wide range of process industries – even India’s space missions – in need of components that principally ensure safety where the slightest risks must be ruled out. Several successful joint ventures have followed Durametallic India (now Flowserve Sanmar).

Sankar has over the decades ensured that these joint ventures with global corporations are models for emulation. He has clearly enunciated a joint venture philosophy which can be summarised somewhat on these lines: Both partners should appreciate the need for the joint venture. They should clearly agree on the way the JV will be managed, they must work towards a system based on trust and transparency. There must be appropriate interaction at different functional levels for the ongoing operations of the JV, and clearly defined high level contacts at both ends for management decision-making on important issues calling for the involvement of both partners. Finally, both partners need to be equally able to serve the growing capital needs of the JV as it expands.

Always leading the way with its concern for the environment, the chemicals division of Sanmar under Sankar has made a fine art of ZLD or zero liquid discharge at its manufacturing facilities, amidst a whole slew of steps taken to ensure sustainable growth.

Corporate governance is an article of faith with Sankar, who must count among his contribution to best practices in business and industry the manner in which Sanmar has evolved a clear-cut management philosophy, its HR policy based on competence and a performance culture, and an elaborately spelt out ethics manual that guides employees on how they can implicitly follow the group’s code of conduct in a variety of circumstances that they may encounter.

Identifying the right person for the right job and empowering his employees to function competently and ethically without fear seem to come naturally to Sankar.

“Strictly follow the law of the land, so that we can all sleep well at night” could well be defined as his paramount mantra to them.

Make no mistake, N. Sankar is a tough, demanding boss. Tasks must be completed in the proper timeframe, decisions should be based on irrefutable logic, information should be communicated clearly, honestly, and such communication has no hierarchy. It only takes him a couple of minutes to see through bluff and inadequate preparation for meetings. He is a master of follow-up, not for him dereliction in the guise of delegation. His attention to detail and meticulous planning do rub off on his managers who are empowered to discharge their responsibilities fearlessly, for so long as they do all that is required of them sincerely, failure will not be punished.

Sankar is known for his steadfast friendships and loyalties. Just as he treated S. Ramaswami, his first, and only, boss with due respect until his retirement, he developed strong bonds with his mentors and senior colleagues. If he found in any of them qualities that could serve the group well, he took advantage of their expertise and wisdom for as long as possible. His professor Dr. G.S. Laddha was one such person of eminence who served on the Chemplast board of directors for more than three decades. For all that his decisions seemed based on cold logic, they could be, and often were, tempered by the human touch – without prejudice to business sense. A sterling example was the way Sankar and his father Narayanan rallied round senior employee S.R. Seshadri, devastated by the loss of his wife while he was at Mettur working for Chemplast. They assisted his relocation to Madras and psychological rehabilitation by approving his pet project to manufacture mechanical seals, vital components required by Chemplast and the process industry in general. The end result was the joint venture Durametallic India. Firmly of the belief that public recognition and approbation are more important than monetary rewards, Sanmar not only honoured him properly during his tenure there but also posthumously by the establishment of the SR Seshadri Training Institute for its employees. Sankar also never hesitated to utilise the services of his most accomplished colleagues beyond their retirement age. Examples are S.B. Prabhakar Rao, M.N. Radhakrishnan and R. Kalidas. He also did not hesitate to reopen Sanmar’s doors to employees who left the group when they sought reentry if he felt they could serve Sanmar well all over again.

The recipient of honours and awards of every description including lifetime achievement awards from state level and national level apex bodies for the chemical industry, Sankar has been a highly respected figure while helming such bodies as Assocham, the Madras Chamber of Commerce and the Madras Management Association, besides sports bodies like the Tamil Nadu as well as the All India Tennis Association, the Madras Cricket Club and Tamil Nadu Cricket Association.

A keen sportsman, Sankar had to forego his ambition to become a top flight cricketer after polio struck him when he was 17, but a doubles champion at the university level partnering N. Srinivasan of India Cements, he continued his love affair with tennis well into his sixties, playing regularly at the Madras Cricket Club courts finding in it the perfect relaxation after a hard day’s work.

It is very well known that Sankar has been one of the finest patrons of cricket in India. The Sanmar family started supporting the iconic team Jolly Rovers Cricket Club in 1966, when India Cements adopted the team and hired cricketers from far and wide inviting players from other states like Mysore and Andhra, with the company’s director K.S. Narayanan enthusiastically leading the search party, as it were. Jolly Rovers dominated Madras cricket for many years, sweeping the league title repeatedly.

The golden jubilee of the Sanmar family-Jolly Rovers association was made memorable by an emotional gathering at Chennai of all living members of that first champion side in July 2015 and exactly a year later by the release by the great all rounder Kapil Dev of a book Cricket for the Love of it to commemorate this record association, accompanied by a presidential lecture by historian Ramachandra Guha.

The inaugural K.S. Narayanan Memorial Oration was delivered on January 30, 2016 by former England cricket captain David Gower. Every year since then, the Oration has maintained its high standards in both the quality of discourse as well as the unimpeachable credentials of the speakers. The crowning glory was the K.S. Narayanan Centenary Oration by former British Prime Minister David Cameron on January 30, 2019.

Sankar has never done anything by half measures and the way he has honoured his father’s memory is second only to the devotion with which he cared for him in his lifetime.

With son Vijay Sankar ready to take over from him whenever he is ready to hang up his boots, Sankar can look back with satisfaction at his journey as entrepreneur, institution builder and enabler of human potential in diverse fields.

Wednesday, November 11, 2020

Thursday, October 29, 2020

Saturday, September 19, 2020

Wednesday, September 16, 2020

Tuesday, September 15, 2020

Thursday, September 10, 2020

Thursday, September 3, 2020

'PROUD OF MY HERITAGE' : KALLICHARRAN

(An interview I did with Alvin Kallicharran in 1992.)

I am very proud of my Indian heritage. I don't know whether my Indian origin had anything to do with it. But Viv Richards made a statement a couple of years ago that he was happy the West Indies was at last a full African side. That is not the way the West Indian captain should speak. Especially in my country, Guyana it is a very insensitive thing to say in view of the political situation there. Viv really hurt the Indians in Guyana.

THE BEST TEST UMPIRE INDIA NEVER HAD

IVATURI SIVARAM

By V Ramnarayan

Starting

unusually young and performing with distinction for three decades, Sivaram was

in a manner of speaking an umpire in the S Venkataraghavan mould, tall and

erect, intensely focussed on his job, firm in his decision making based on

sound theoretical and practical knowledge. In the early part of his umpiring

career, he was often younger than the players in the matches he was officiating

in, though evidently quite unfazed by that. His confidence and integrity stood

out so clearly that few players, if any, questioned his decisions, while few of

his decisions left room for dissent.

I was

always an admirer of Sivaram who stood in some of the matches I played in the

1970s. I was so impressed that I expected him to walk effortlessly into

international duty. Little did I know then that he would receive a raw deal in his career, that

umpires too were like players subject to the whims and fancies of authority, that

Sivaram would one day be “hanged without a trial,” (the headline of a TOI story

by Sumit Mukherjee of how Sivaram was axed from the ICC panel of TV umpires

without a single opportunity in a whole series) much in the manner of players

who move in and out of a 15-man squad without playing a single match on a whole

tour or in a complete tournament. Though Sivaram officiated in ODIs in India,

his Test chances never came, not even after he was unofficially asked to be

ready to umpire in a particular Test match in 1986. Not unusual in Indian

cricket, the job went to another, senior, umpire who pleaded for one last game.

“Sivaram was after all young, with a bright future ahead of him, so he could

afford to wait,” was the argument. The Test match debut never came.

Mrs I Chellayi was an A grade artiste of All India Radio and a lecturer in the

Government Music College of Secunderabad. Sivaram joined the college as a

student at age 12 and completed a three-year certificate course. He was only 22

when his hero Chittibabu allowed him to accompany him on the veena in an album

entitled Musings of a Musician, in which the percussion accompaniment was

provided by eminent musicians Guruvayur Dorai, Kamalakar Rao and Manjunath. Sivaram

cherishes the memory of “the experience of practising with my guru and those

stalwarts.”

Sivaram

was undoubtedly a boy prodigy. And not just in music, for he first umpired in

the Moin-ud-Dowla Gold Cup tournament of Hyderabad when barely 17, even before

he had formally qualified as an umpire. His inspiration came from his father,

the late IVS Sastry, an enthusiastic amateur sportsman and umpire in the

Hyderabad cricket league, and his uncle, the late Ramana Rao a BCCI umpire.

Ramana Rao first allowed Sivaram the opportunity to co-umpire a local league

match with him when he was just 15. “You will be a better umpire than player,”

he told the young wicket keeper-batsman, and before long, he was standing in

that Gold Cup match in 1971, thrilled to watch the greats of the day like ML

Jaisimha, Hanumant Singh, EAS Prasanna, BS Chandrasekhar and GR Viswanath from

close quarters. A rare combination of cricketing genes and musical genes,

Sivaram owes much in his growth as an umpire to Ramana Rao and Test umpire VK

Ramaswamy, his “role model.”

Having qualified as a BCCI panel umpire by

1978, Sivaram made his Duleep Trophy debut in 1986, and did his first ODI in

1994. He made steady progress and earned

appreciation at every stage from players, officials and visiting commentators.

A memorable stumping decision involving New Zealander Roger Twose in a 1995 ODI

that he made without referring to the TV umpire won him compliments from

commentator Ian Smith and match referee GR Viswanath. English umpire David

Sheppard was one of his seniors who had a good word for him. An unforgettable

moment came during his Duleep Trophy debut, when his explanation of Sunil

Gavaskar’s dismissal on 94 earned him an approving nod and a tap on his

shoulder. “How did I miss that ball?” the Little Master had asked the young

umpire.

It

must be a huge disappointment not ever officiating in a Test match, a rude

shock to have been dropped from the ICC Panel without a single opportunity to

prove himself on the field, but Ivaturi has taken all that on his chin like a

good soldier, secure in the knowledge that he performed admirably throughout a

distinguished umpiring career in first class matches, mentored umpires through

workshops, officiated in the inaugural IPL season and contributed in numerous

ways to improvement in umpiring standards. Now in his second innings as a

musician, he has always enjoyed the blessings of his mother who at 90 still

mentors him, and the lifelong support of wife Venkataramani and brother Kanakachalam

in all he does.

Friday, August 28, 2020

CS DAYAKAR

A Feisty All-rounder

By V Ramnarayan

Sometimes we tend to forget

quiet interventions by individuals that have life-changing impacts on our

lives. I for one have been guilty of failing to mention the crucial role CS

Dayakar, my friend and spin twin of the 1960s, played in my cricket career

while writing the story of my days as a cricketer. Looking back more than fifty years on, I realise what a gross omission that was, comparable to the lack

of selectorial recognition that prevented Dayakar from exhibiting his sterling

qualities as a left-hand all rounder to wider audiences than the

spectators watching college and league cricket in Madras during the two decades

he was active in them.

I first met Dayakar at

Vivekananda College during our Pre-University Course days in the academic year 1963-64.

We knew each other as decent cricketers, but did not have too many interactions

as we were in different groups, and while I think he was a member of the college team,

I was not. I went on to Presidency College next year, and miraculously got

selected to the college cricket team thanks to the efforts of two good Samaritans.

The first of them was another left hander ‘Alley’ R Sridhar, who made sure I

attended the selection trials after I had gone to college that day without my

cricket kit, positive that I stood no chance of being picked. Living much

closer to college than I, Alley rushed home during lunch and brought me white

trousers and canvas shoes and dragged me forcibly to the nets in the evening.

The second benefactor was the late Ram Ramesh, the captain of the Vivekananda

College team, who in the previous season had failed to convince the Physical

Director that I was good enough for his squad, and felt guilty about it. (It

was his recommendation that had facilitated my turning out, quite successfully,

for Jai Hind CC in the Madras league that same season). Ramesh was a towering

presence—literally—at the Presidency selection nets, where he stood next to

captain Bhaskar Rao and senior player Rajamani and brainwashed them into including

me in the team.

Dayakar had meanwhile lost a

year by missing the PUC Sanskrit exam. He too joined Presidency next year, in

the BSc Geology course, if I remember right—to my Chemistry major. I was a

veteran of one season when he became my teammate in the academic year ’65-‘66,

and we eventually forged what was arguably the most successful spin pair in

Madras’s college cricket circuit for the next few years. There were quite a few

class acts around, S Venkataraghavan, for example, leading a superb Engineering

College attack, but few were limited to a pair of spinners as we were, though

we too were for a while bolstered by the presence of a third spinner—in leggie PS Ramesh.

Dayakar was an accomplished

all rounder, a gutsy one who invariably reserved his best for the toughest

opposition. He belonged to a family of talented cricketers. His brothers

Ekambaram, Kothandaraman, Padmanabhan, Umapathy and Kadiresan were all

competitive and more than competent players. A couple

of them played first class cricket, Umapathy has for long been a coach in the

MRF Pace Foundation, while the youngest brother Kathiresan, an excellent

off-spinner-all rounder, was distinctly unlucky not to graduate to Ranji Trophy cricket.

Dayakar bowled his left arm

spin in a lovely arc, with a whiplash of an action that made the ball hurry off

the wicket. His length and line were spot on, and the batsman had to

contend with an awkward length that could create an optical illusion in

the batsman. Our captain Ram—N Ram of The Hindu family—relied on him a great deal,

sometimes bringing him on with the new ball. When the shine was still intact, Dayakar

bowled a deadly in-swinger to the right hander. He was in short a captain’s

best friend who posed a complex mixture of problems to batsmen. I regarded him as a better bowler than me in our college years, and I always

tried to play catch-up. He was the catalyst who—by both example and verbal

encouragement—constantly pushed me to improve. We backed each other wholeheartedly

and the outcome was a formidable combination that, with enthusiastic support

from the fielders, won many a match for the team. Dayakar’s batting too was top

class at that level—he rarely played at higher levels. He and other batsmen

like John Alexander and Alley Sridhar were consistent scorers against strong

teams, with all rounders Rajamani and SV Suryanarayanan chipping in creditably,

especially if we lost our star batsmen like Ram and Premkumar early. After these leading batsmen left college, we

found fresh batting talents in the likes of MS Rajagopal and the lefthanded ‘Chama’

K Swaminathan.

Dayakar also pushed me hard

to contribute in the batting department. We enjoyed some useful partnerships,

even if the running between the wickets at his urging nearly caused my lungs to

burst. It was an early wake-up call that forced me to work on my stamina and

physical fitness. Though I made some runs, I was never in his class as a

batsman.

Now for the crucial interventions Dayakar made in my cricket career. After my undergraduate degree, I was working at the desk in the Indian Express. It was work I had an aptitude for and enjoyed thoroughly, but I was unhappy enough with an instance of office politics to want to quit. At that precise moment came an invitation from Dayakar and the Presidency College Physical Director to go back there and do post graduate studies. With no prospect of playing serious cricket if I continued as a career journalist, I made the right decision in going back to college, as later events proved. With Dayakar and I enjoying elder statesmen status by now, we both thoroughly enjoyed resuming our partnership. Unfortunately, I had to discontinue my MA programme when my father’s poor health required my presence with the family at Calcutta, where Appa was working for Bank of India. By the time Appa got better, the first year MA exams were over, and I thought, “There goes my MA.” Dayakar waved his magic wand once again, and the college welcomed me back, allowing me to carry the three papers I had missed into the second year. Followed an excellent season for both of us, with several stellar all round performances by Dayakar ensuring that our relatively weak team often fought strong opposition gallantly and brought off a few unexpected wins. Leading the side, I had the great satisfaction of watching the considerable improvement of many newcomers we managed to enable.

One of

the open secrets of our success that season was that Dayakar and I bowled every

over from the time ‘Play’ was called in every important match, but allowed the

others totally free to “express themselves” in 90% of all our matches, never

yielding to the temptation to pick up relatively easy runs or wickets for

ourselves. This was Dayakar’s brainchild, and I carried out the plan with

conviction, but I regretted the strategy when I looked back on the season in

later years, because it denied some good bowlers like PS Venkatesh, Osman Ali

Khan and Kasi Viswanathan opportunities to prove themselves in stiff contests.

Dayakar and I were both

selected to represent Madras University in the Rohinto Baria Trophy matches

played at Dharwar, Karnataka, but my spin twin declined the offer fearing that

he would not find a place in the playing eleven. I was disappointed with his

decision, because I was keen to continue our bowling firm, which was now a

well-oiled machine of five years’ standing. I had a reasonable if unspectacular

outing for the university.

Dayakar’s final intervention

in my career: Despite consistent success in college cricket for four

consecutive seasons, I had been content to play in the lower divisions of the TNCA

league, partly because I believed some people I trusted when they told me I was

not ready yet for the First Division. Nothing could have been more absurd, and

I was missing opportunities by underestimating my ability. It was Dayakar who

bulldozed me at the start of the 1969-70 season into joining him at Alwarpet CC

being led by our former college captain

N Ram. That was the first tentative step I took towards entering first class

cricket.

I left Chennai in December

1970 to join State Bank of India in Andhra Pradesh, and wound my way soon to

Hyderabad, where I made my Ranji Trophy debut nearly five years later, after long

struggle. Dayakar joined Indian Overseas Bank, Madras, where he was a key

member of the cricket team for a long time. Busy with my own cricket, family and

banking career, I no longer followed Dayakar’s cricket closely. Was he ever

considered fit material to represent the state in first class cricket? I have

no doubt in my mind that Tamil Nadu let him and itself down by failing to

acknowledge the merit of this fighting all round cricketer.

Sunday, August 9, 2020

Saturday, August 8, 2020

SO NEAR YET SO FAR

Jyothiprasad’s narrow miss

By V Ramnarayan

The scorecard does not always tell the whole story. For

example, the card for the second innings of the Kerala vs. Hyderabad Ranji

Trophy match at Warangal in the 1976-’77 season opened with the bland statement

OK Ramdas/ caught Narasimha Rao/ bowled Ramnarayan/ 22. It failed to mention

that the catch was off a ricochet after Ramdas picked me from outside the off stump and nearly decapitated short

leg Jyothiprasad with an almighty sweep I can still hear 44 years later. Poor

Jyothi, my partner in crime on so many occasions, with his brilliant close-in

catching, rarely took early evasive action, preferring to keep his eye on the

ball longer than most other short legs. This time OK gave him no chance, and I thought

I would never be able to bowl again, so distraught was I. Joe, as we called

him, was leaving for Baroda the next day to represent South Zone in back to

back Deodhar Trophy and Duleep Trophy matches against West Zone. He left the

field immediately after the injury, probably on a stretcher, and once in the

dressing room, treated himself to some

inspired self-medication—a quarter bottle of Hercules XXX rum neat. All of us

followed Jyothi’s fortunes anxiously after we disposed of Kerala and returned

to Hyderabad, and we received both good news and bad news. Jyothi had a

spectacular Deodhar Trophy match with five wickets, including the prize scalp

of Sunil Gavaskar, whom he bowled for zero. His Duleep performance could have

been equally dramatic—with a little bit of luck. He bowled the first ball of

the West Zone innings, and surprised by a powerful straight drive, dropped the catch. The

batsman was again Sunil Manohar Gavaskar—who went on to make 228. Earlier, Joe

(40) had been involved in a fighting eighth wicket partnership of 102 with

Brijesh Patel (85) in South Zone’s first innings total of 236.

Coming back to the Warangal match, I had a decent match with

the ball except for the injury to Joe, with 4 for 31 and 1 for 1. I however sustained

a bruised ego, because I had always prided myself on my clean record of

close-in fielder safety while I was bowling. (The only other aberration

occurred years later in a local match at Chennai, the unlucky short leg this

time MA Sriram, a talented left handed all rounder who now lives in the US).

Ramdas was not the only sweep specialist in the Kerala side. The talented

Ramesh Sampath, a cousin of S Venkataraghavan, and an engineer working at ISRO,

was making waves with his attacking batsmanship. A compulsive sweeper, he had

an excellent record against the Karnataka and Tamil Nadu bowlers whom he must

have irritated with his irreverent shotmaking regardless of the bowlers’

reputation. Thanks to my captain Jaisimha’s expert mentoring, I knew a thing or

two about how to counter sweep specialists. Ramesh was a good friend, and in

the course of breakfast table banter, he said to me, “Ram, don’t get me out

today.” Remembering that he had got out to me sweeping on my debut the previous

season, I shot back, “Don’t sweep me, and I promise not to get you.” Sure

enough, when he came into bat, Ramesh swept me first ball—straight down square

leg Noshir Mehta’s throat. Ramesh seemed to have a bright future in cricket,

but tragically drowned at a Goa beach a couple of years later.

My debut season had been a happy experience, and team morale

had been pretty high, umtil we crashed out in the quarter finals after gaining

a first innings lead against Bombay. This year, I had missed the disastrous

season opener against Andhra at Eluru, away playing for Rest of India versus

Bombay in the Irani Cup at Delhi. When I joined the team at Warangal, I found a

strange mood of negativity and what seemed like lack of cohesion following an

alleged attempt by wicket keeper to replace Jaisimha as captain. It was all

very disappointing. Murti was a close friend of mine and quite a protégé of Jai

as well. Playing for Hyderabad was never again going to be as consistently

fulfilling and thrilling as during my first season, though there were to be

many happy moments along the way. Tiger Pataudi and Abbas Ali Baig had retired

at the end of the previous season, and Jaisimha would hang up his boots at the

end of this one. He had led the team for nearly two decades.

Sunday, August 2, 2020

Saturday, August 1, 2020

VARALAMA?

Sarvam Thaalamayam

A Film by Rajiv Menon

I finally got round to watching Rajiv Menon’s inspirational feature film Sarvam Thaalamayam (STM), a sensitive treatment of the subject of caste and elitism in the world of Carnatic music, the classical music of south India. It also highlights the sweet taste of success that passion and love for your art can bring against all odds, and despite chicanery and opposition at every stage.

The movie is about

the obsession of a young lad hailing from a dalit Christian family—mridangam

makers for generations—with learning to become a concert percussionist in

Carnatic music. Rejection and ostracism all round, with his parents and finally

even his compassionate guru joining in a shattering chorus of disapproval, almost

crush his dreams. He despairs of ever finding a teacher as great as his

erstwhile guru, but in a moment of epiphany, follows the selfless advice of his

godsend of a girlfriend and seeks teachings from the bewildering variety of

musics—folk, devotional, romantic, martial, festive—that India abounds in. The

miracle that reunites him with his guru who relents from his earlier orthodox

contempt for reality shows and trains him for one, and the boy’s eventual

triumph in the contest make for a memorable climax. In the finale, even a wily judge

opposed to him is moved enough by Peter’s extraordinary originality (inspired

by his eclectic journey of discovery) to award him a perfect ten.

The movie does not follow a hardline narrative. Nowhere is

caste even mentioned. Though we know from Johnson’s name that he is Christian,

we only learn he is dalit by inference—the community are known in the south to

be makers of the mridangam requiring the usage of the skin of cattle, and Peter

and Johnson Senior are served in plastic cups, not the usual glasses, in a

teastall. What I like even more are the lack of condescension in the manner the

screenplay treats the protagonist’s hysterical affiliation to popular film star Vijay’s fan club and the absence

of melodrama in scenes showing blood donation to child cancer victims and other

good deeds of the street fighters of the movie. Of humour, there is no

shortage. As when the venerable mridangam guru fails to suppress his mirth at Peter’s instant

recognition of Vijayadasami day. “June 22, sir, it is Vijay sir’s birthday!”

Even Mani, the most villainous character of the film is not all

bad. Here again, the director makes no attempt at showing ‘the villain’s’

transformation when he redeems himself in the final scene after scheming to get

Peter defeated by his disciple—one he stole from under his guru’s nose. He is

instead seen as won over by the sheer brilliance of the new champion’s

percussion. The loser, too, is a gallant runner-up, not an object of ridicule.

Rajiv Menon has extracted exceptional performances from an

ensemble cast coincidentally represented by the greatest diversity of caste and community imaginable. Nedumudi Venu breathes life into the role of eminent mridanga

vidwan Vembu Iyer, an unbending traditionalist wedded to his art, who can spot

talent no matter where it resides, while Vineeth as his senior sishya Mani jealous

of new arrival GV Prakash Kumar is unrecognisable from the matinee idol we have

known in the past, Prakash himself effortlessly straddles multiple

personae from Vijay fan through hip hop drummer to street fighter to obsessive

convert to the magic of classical mridangam and Kumaravel is effortlessly credible

as Johnson, the inheritor of a legacy of mridangam-making that allows him no

self-indulgence, no illusions about acceptance into the exalted world of

classical music. Sumesh Narayanan, an accomplished vidwan of NRI origin, brings

dignified credibility to his role. Shanta Dhananjayan and Aparna Balamurali

quietly lend substance to their roles as the women who intervene strategically

in Peter Johnson’s journey towards fulfilment. Vocalists Unnikrishnan, Sikkil Gurucharan and Srinivas play delightful cameos as judges at the reality show. The music direction by AR Rahman

is impeccable and appropriate scene for scene, shot by shot. The Carnatic music

segments are totally authentic, with no attempt to woo the box office.

The main reason why I took so long to watch STM was that I

mistook it to be a new avatar of a Rajiv Menon-made documentary on mridangam

maestro Umayalpuram K Sivaraman, which I had seen a few years ago. I was

delighted to see UKS’s name in the credits to STM. His inputs and personal

example are clearly evident in the film. Sivaraman did impart his art to his

dalit mridangam maker’s son, didn’t he?

I think STM is an important step towards inclusiveness in

classical music. Elitism and casteism are indefensible in any walk of life, but

to paint whole generations of classical musicians as blatant perpetuators of

discrimination and indulge in strident name-calling would seem to be just so

much posturing rather than a sincere attempt at reform. The enlightened among

our musicians, in both the north and the south, have embraced diversity in their

art as well as their fellow artists. STM ends on a positive note, which is not

to say that it offers easy redress to centuries-old injustice. Instead, it

suggests that together we can overcome rather than annihilate.

In an online or TV discussion, Rahman and Menon disclosed that the

film was originally tentatively named “Varalama?” the opening word of the beautiful

title song, apparently inspired by Gopalakrishna Bharati’s classic ‘Varugalano

Ayya’ from the movie Nandanar Charitam. While Nandan’s song in Dandapani

Desigar’s bell-like voice was a plaintive appeal to Nataraja to let him enter

the Tillai temple, ‘Varalama’ is a plea by an outsider to be admitted to the

exclusive sanctum of classical music. ‘Varalama’ more accurately describes the story

of Johnson’s yearning than ‘Sarvam Thaalamayam’, which stresses the presence of

rhythm in every aspect of life.

V Ramnarayan `

Friday, July 31, 2020

BABUJI

Life with Grandma

By V Ramnarayan

My late friend Mohan Ramalingam, then secretary of the Mylapore Club, brought me my fifteen minutes of fame as moderator of a Chess-Bridge conversation on stage between Viswanathan Anand and KR Venkataraman about a decade ago. Both the speakers were extremely articulate and passionate about their sport, with Anand frequently bringing the house down with his scintillating wit. Among other things, he gave us an elaborate description of the enormous amount of team work that goes on behind his major campaigns including the computer analysis of hundreds of games involving Anand as well as his opponents, and the intricate post mortem that follows his most recent contest. Anand could not suppress a smile when I reminded him of his earlier statement that chess was a lonely game. Women's chess was one of the topics of the evening, and while the question of why in a mindsport, no woman had so far been crowned world champion against all comers, men or women, came up, Anand expressed the hope that such a prospect, though distant, was not to be ruled out with more and more girls taking to chess the world over.

Anand regaled us with some hilarious stories. One of them involved a train journey during his childhood. “What do you want to be when you grow up?” asked an older co-passenger.””A chess player, “ was the instant reply from the boy. “I understand. You love chess, but it is a hobby, a sport. What do you want to do after you graduate? What do you even want to study, engineering, medicine?” “Play chess,”Anand, the junior national champion persisted. Finally the man gave up. “Do you think you are Viswanathan Anand?” he blurted out.

My mind went back to a train journey in the mid to late 1970s. My daughter Akhila, all of four or five, was travelling with her mother Gowri from Hyderabad to Bombay. It was August 15 and one of the ‘uncles’ in the compartment asked Akhila, “Do you know why today is a special day?” “I know. It is Independence Day. My grandfather got us independence from the British,” my daughter informed her by now growing audience. The uncles were pleased no end. “Yes, Gandhiji was your grandfather, my grandfather, everybody’s grandfather,” one of them piped in.

Little did that group of patriotic Indians realize that Akhila was actually referring to her great grandfather Kalki Krishnamurthi, the famous author and freedom fighter. Mrs Kalki, Rukmini Ammal, widowed in 1954, came to live with us in Hyderabad when Akhila was a baby, and took firm control of her education even before she started school. That is how little Akhila came to speak Tamil fluently and like a proper mami typical of Tamil households. “Appa, Amma, come out and watch iyarkai arpudam (nature’s miracle),” was par for the course every time Akhila wanted us to share in her excitement in watching a flower or a bird or a sunset.

And Babuji—as we called Gowri’s late grandma, and thereby hangs a tale, to be told later—completely brainwashed the child into believing that Kalki was the greatest hero of India’s freedom struggle, India’s finest writer, besides being the perfect family man with unsurpassed virtues. With such a hard act to follow, Gowri and I were constantly up against it as young parents.

We once had two American girls staying with

us in our tiny three room apartment. Mornings were hectic with Gowri busy in

the kitchen and multitasking, and me getting ready to go to work. The guests

were sipping their tea daintily while the pop-up toaster failed to pop and the

toast was burning and sending smoke and flames heavenwards. All the ladies needed to do

to put out the fire was reach out and switch the toaster off. Instead, they sat

there and gently called out “Go-owri! Go-o-owri!” while Gowri was battling with

her kerosene stove in the kitchen. Babuji chose that moment to make a dramatic

entry. She gave the girls the angriest glare she could muster, stood there with

her arms akimbo and declared in her deepest, grimmest voice:”Rotti pinishdu!”

Thursday, July 30, 2020

LIFE BEGINS AFTER TEST CRICKET

A "Novella" By Carolyn Gupte

The Story of Subhash and Carol Gupte

The romance of cricket has always held an irresistible

attraction for me. The on-field exploits of its greats and not-so-greats that

ensure the glorious uncertainties of the game have never needed the collateral

support of love stories beyond the game to cast a spell over me. True, one has

been aware that some great romances through the ages have served to enlarge the

aura around some of our most enduring icons, but I have rarely been curious to

know the details of the love lives of my cricketing heroes—until the daughter

of one of the all time greats of Indian cricket and his West Indian wife of

Indian origin decided to ‘semi-fictionalise’ the classic love story of her

parents. It is a story of the overwhelming odds they had to fight to marry each

other, of their steadfast devotion to each other, of the depth of their

feelings for each other.

The premature end of Subhash Gupte’s Test career was not

only one of the great tragedies of Indian cricket but also an example of gross

disrespect and rank injustice, by an uncaring, insensitive administration. After

watching his series-winning exploits in the 1955-56 season against New Zealand—overshadowed

only by the Mankad-Roy world record opening partnership—on my debut as a

spectator, I had come to expect nothing short of greatness from this diminutive

wrist spinner Sir Garfield Sobers rates higher than Shane Warne. Gupte did not

disappoint. His 9 for 102 in the Kanpur Test against the all-conquering West

Indies was the best of his heroic bowling performances in that series, but the

visiting batsmen led by Garry Sobers and Rohan Kanhai stole the rubber away

from India with some magnificent batting that rode a wave of hostile bowling by

the likes of Wes Hall and Roy Gilchrist. The Madras Test of that series was the last

time I saw Gupte in action, and with a four-wicket haul in the second innings,

he did not disappoint me, his young hero-worshipper.

It was during the 1961-62 tour of India by Ted Dexter’s MCC that

the cricket board destroyed Gupte’s Test career in one fell swoop on

disciplinary grounds. He and roommate AG Kripal Singh were suspended following

an alleged act of indiscipline in which Gupte had no part. While Kripal came

back into the Test team a couple of years later, Gupte emigrated to the

Caribbean with his wife Carol, whom he had married on 1st April

1957. She had been Carol Goberdhan when he first met her on the 1952-53 Indian

tour of the islands, a tour during which he had been quite the star attraction.

At age 33, he had played his last Test match, and barring local games in

Trinidad, the only cricket he would continue to play consisted of his

professional Lancashire league stint with Rishton, where he spent a happy time

with his wife.

Upsetting as it was to find Gupte’s name missing among the

dramatis personae of India’s Test performances, I soon learnt to discover new

Indian heroes even during the disastrous tours of the 1960s. Gradually, one

became accustomed to his absence in the Indian team. To learn that ‘Fergie’

Gupte and his wife played host to Ajit Wadekar’s men in Trinidad in 1971, or

that every visiting Indian cricket team made its pilgrimage to the Gupte home gave

one no hint of the romance and longevity of their relationship, nor of the

opposition the couple had had to face from their families during their

courtship.

A large gap in one’s insights into the Gupte adventure has

now been filled by reading Love Without

Boundaries, the affectionate retelling of ‘the 49-year partnership of Subhash

and Carol Gupte’ by their daughter Carolyn Gupte. The novella, as the author

calls it, is not the story of Subhash’s stellar cricket career, but a moving

account of the family values, strength of character and singleness of purpose

that went into their journey together, Gupte’s pride in his wife’s many

accomplishments crowned by her successful running of the school she established

in September 1972, AC Goberdhan Memorial School, and his wholehearted support

of all she did. It is also the story of the tremendous fight Carol made to

rebuild her life after suffering the worst injuries in a horrendous car

accident involving her, Subhash and daughter Carolyn in 1977.

‘Outfitted with a skull cast”, Carol was hospitalised for

three months, but once discharged, made a strong comeback. “With skull cast

firmly in place, and jaws wired shut, she returned to work and conducted the

daily business of running her home and school from an upstairs bedroom at Five

Gables, the original family home where the school was located. In 1987, after

the Guptes moved into their own house, Subhash sustained a crippling hip injury

that made Carolyn—who had graduated in London—decide to give up her burgeoning

public relations career to become her father’s primary caregiver, playing that

role to perfection till his death in May 2002.

Make no mistake; this is a love story, an unusual one in

that it is told by the daughter of the protagonists. The hero and heroine are

very special people, achievers in their chosen fields. There is no attempt in

it at establishing the greatness of Subhash Gupte, the world class leg spinner.

It is as if the author believes the reader knows that and does not bother describing

his art. The book is about the Guptes as flesh and blood people, vulnerable,

“flawed” even, about their total love for each other and their families. For

Carol, life with Subhash had been “a constant barrel of unexpected surprises and

a bellyful of spontaneous laughter—(he was) an imperfect man, a flawed man,

but… blessed with such a good heart…”

Carolyn Gupte writes effortlessly. Her admiration for her

subjects is obvious, and she writes glowingly of her parents, miraculously

avoiding sentimentality. The book has the makings of an engaging film script.

An altogether lovely read.

V RAMNARAYAN

Wednesday, July 29, 2020

MUSIC KEEPS HIM ALIVE

TANJAVUR SANKARA IYER

By V Ramnarayan

I reproduce here a tribute I wrote many years ago to one of Carnatic music's living greats.

“Look

up the meaning of the Tyagaraja kriti Sangita gnanamu in the book there ,” the

frail old man bundled up and blanketed in the chair in front of me said, a

minute after I entered his bedroom in his nephew’s house inside Sankarnagar,

Tirunelveli, when my friend Sampathkumar and I visited him earlier this month.

Near-nonagenarian and confirmed bachelor Tanjavur Sankara Iyer may be a very

sick man today, needing the constant care of a loving nephew, his wife and his

daughter, but his musical creativity and devotion to past masters including the

Trinity remain undimmed. True to the words of Tyagaraja, he still pursues

sangita gnanamu with fervent devotion, still composes his own bhava-rich

compositions and still sings and teaches everyday. The object of his love and

affection and guru kripa is his 12-year-old granddaughter Aparna, on whom he

pins his hopes for the future.

For those unfamiliar with Sankara Iyer’s contribution to Carnatic music, I

reproduce below a brief extract from a Sruti (issue 195) profile of the vidwan

by Lakshmi Devnath:

"Sankara Iyer is a highly respected vaggeyakara. His compositions have

been a source of delight both to the vidwans and to the general public, but he

himself speaks with great modesty about his works. “I should not be bracketed

with the Trinity or other famous composers of the past. But I can say my

compositions are rooted in sampradaya, as theirs are, while they cater at the

same time to evolving needs without being light. Shall I say, my compositions

are a bridge between the old and the new!”

Anyone who has listened to Sankara Iyer’s vocal concerts, lec-dems and his own

compositions, will readily agree that he is indeed a bridge between the old and

the new.

My planned interview with Sankara Iyer never took place, because, thrilled to

meet visitors from Chennai, he was keen to demonstrate his granddaughter’s

singing, and more important her ability to absorb his lessons on sruti suddham,

raga lakshana, and clear enunciation of sahitya. He stressed the vital

importance of the last of these aspects of music, but was quick to point out

that on his list of priorities, the raga overrode the bhakti emanating from

understanding of the lyrics. “The lyrics could be about Rama, Krishna or

Karuppannasami; it’s the musicality that matters.”

We were fortunate to catch glimpses of his highly evolved sense of aesthetics

through his profound enjoyment of the beauty of both verse and tune, whether by

the Trinity, Sankara Iyer himself or Kalki Krishnamurti, whose Poonkuil koovum

pooncholaiyil orunal, he taught Aparna with obvious relish. “What a wonderful

poet!” he exclaimed.

When I reminded him about a T Viswanathan concert he had attended more than a

decade ago at my Chennai home after which I dropped him home, he instantly

recalled, “Muktha was in the audience, wasn’t she? And I remember she joined Viswa in a song

whose words he momentarily forgot. In the car, you asked me if I would perform

at your residence. What happened to that offer?”

That was indeed a doosra from the veteran. I had no answer to that.

Saturday, July 25, 2020

Thursday, July 23, 2020

Wednesday, July 22, 2020

Thursday, July 16, 2020

Wednesday, July 15, 2020

MARTHANDA VARMA

A Gracious Ruler

By V Ramnarayan

I am no fan of royalty, though I used to believe in the

superstition that that was the way authors were rewarded by publishers. I have certainly

not been in awe of princes, nawabs and rajas, with the notable exceptions of

Ranji, Duleep, Pataudi and Hanumant Singh. It was but natural for me then, when

invited to be part of a weeklong celebration of the GNB Centenary in January

2010, each day inaugurated by an erstwhile raja or maharaja of one of India’s

princely states of yore, not to be overly excited. I had around the time

embarked on the enjoyable adventure of translating into English a slim biography

of the iconic GN Balasubramaniam, the matinee idol among the great 20th

century Carnatic music vocalists, and that was enough reason for me attend the

lectures on him every evening.

The princely chief guest on one of those evenings was

Marthanda Varma of the former Travancore court. As I was leaving home for

Narada Gana Sabha that evening, my mother said to me, “If you get a chance to

meet the maharaja, please talk to him about your grandfather. Like everyone in

the family, she referred to her father as Anna, and continued, “After retiring

as Inspector of Schools in Trivandrum, Anna was appointed as the maharaja’s

private tutor for sometime, and Marthanda Varma even mentioned him to a

Malayalam magazine once.”

The programme that evening was pleasant enough and the

maharaja made an excellent speech, keeping it short and sweet. I had no chance

of meeting him, and was sorry I was going to disappoint my mother. After the programme,

I stopped at the open air cafeteria for a cup of coffee, and lo and behold,

someone seated the chief guest next to me while he waited for his car. My

esteemed companion seemed friendly enough, so I made bold to bring up the topic

of grandfather Sivaramakrishna Iyer. The maharaja not only remembered him with

some pleasure, but asked me if I had with me any photograph of him belonging to

that particular vintage. Even as I was preparing to reply, he said he would

send me a photograph of them both. Just then, one of the organisers came over

to inform Marthanda Varma that the car was ready to take him home. “You spoke

so well today, Sir,” he added. “I owe it all to this man’s grandfather Sivaramakrishna

Iyer. He transformed me from an indifferent student into a scholar.”

The promised photograph never came, but I can never forget

Marthanda Varma’s warmth and grace.

‘

Tuesday, July 14, 2020

Sunday, July 12, 2020

Friday, July 3, 2020

A CLASS ACT

MS, apropos nothing

By V Ramnarayan

It was said of Madurai Mani Iyer's music that it pleased not just the connoisseur, but even the man on the street. There's this charming story of a rickshaw puller outside Rasika Ranjani Sabha, Mylapore, who asked a customer to wait while he listened to his Eppo varuvaro (or was it his English note?) Perhaps, the only other Carnatic musicians with such a mass following have been those who first made their name as film singers.

MS Subbulakshmi had a similar impact on lay listeners when her songs in the film Meera took the country by storm. Audiences in the north equated her with the Rajasthani mystic herself, with hundreds of devotees falling at her feet during the shooting of the film on the streets of Rajasthan. Songs like Katrinile varum geetam (in Tamil Meera) and, decades later, Kurai onrum illai have also captured the imagination of millions of fans, affirming the power of emotion and language in making music accessible to common folk. (In the extraordinary reach of these songs lay a huge opportunity to take Carnatic music beyond the confines of elitist audiences, but we have made no effort to convert these fans into hard core Carnatic music rasikas). On the contrary, her immense popularity only gave critics the licence to dub her music as populist, allegedly lacking in the technical sophistication of so-called musicians' musicians, though genuine, unbiased followers of Carnatic music know otherwise.

The large number of mourners who thronged the MS home at Kotturpuram when she passed away in December 2004 came from all social classes. The visitors must have included every musician and every one connected with music, especially Carnatic music. As evening fell, and the cortege was about to begin its slow procession to the cremation ground at Besant Nagar, there was a surge of mourners anxious not to miss a last glimpse of the songstress who had added meaning to their lives. Many apparently poor men and women were part of this group of late visitors, possibly rushing from their labours at the end of the day. Their tears were quiet and dignified, not the kind of breast-beating we are so accustomed to at funerals. When will we see another like her, was the common lament.

These were obviously not her regular concert audiences. What was their connection with her, then? The answer perhaps lay in the devotional music they heard from her cassettes every day of their lives. I remembered the Vishnu Sahasranamam or Venkateswara Suprabhatam in a continuous stream of radio broadcast I heard as I daily crossed a long row of homes in a poor quarter of Tiruvanmiyur on my way to the bus stop. Though MS's charitable work reached vast numbers of people, the poor who came to pay her their last respects were probably not even aware of the extent of her munificence. Many of them were there that evening as a token of gratitude for the solace her devotional music brought them. No matter what their caste or creed, she had touched their lives with the sublime prayer of her songs in several languages.

''It took me a year of practice to get it right.'' This is what a veteran vocalist said at a recent programme that showcased the most striking examples of MS's classicism. Vijay Siva had just been complimented for the majesty of the opening notes of the concert. His statement spoke volumes not only of the humility of this confident, accomplished musician, but also of the needle-sharp precision and resonant sruti suddham of his first phrases Namo namo raghukula nayaka that equalled MS's.

There, however, prevails a quite contrary view among some of the cognoscenti that MS's music was all about her majestic voice. The fact that some of her music appealed to common people not versed in the arts is what must have caused the less than fair high brow critiquing MS received.

Many of the articles the monthly Sruti published during her centenary year tried to right that wrong. They stressed that MS was a consummate musician in the classical tradition, not just a possessor of a golden voice and purveyor of relatively light fare. They spoke of the assiduous practice and systematic preparation that ensured the maintenance of that golden voice in tip top condition all her life, the trouble she took over correct diction and perfection of emphasis on phrases long and short, her understanding of raga both cerebral and intuitive, her refusal to overdo or misuse sangatis, her melodic and rhythmic precision and her complete surrender to the music

Violinist RK Shriramkumar who accompanied MS in many concerts remembers her special qualities as a teacher. "A stickler for perfection and meticulousness, she would grasp every nuance," he said in his Sruti article, and "she would impart with utmost detail and watchfulness, whether it was a special sangati in the kriti Sree Ganapatini she had learnt from T. Brinda, or the need to avoid an excessive gamaka in Todi, or a vallinam-mellinam in a bhajan, or even a silent pause between two phrases in a song."

Young vocalist Navaneet Krishnan, who described MS as an eternal student, marvelled at her breath control. According to him, '' it was almost impossible to hear her taking a breath while singing.'' He described her music as a rare amalgam of voice, veena and nagaswaram.

Author Indira Parthasarathi saw the highest form of spiritual bliss in her ''total identification with the Muse of Melody.''

Seetha Ravi marvelled at her total commitment to her art that made her insist on recording the Vishnu Sahasranamam in one go, the way it ought to be chanted, not over numerous sessions.

Kanniks Kannikeswaran speculated if MS's Vishnu Sahasranamam was heard at any given time in some part of the world, much like the British empire where the sun never set! He spoke of Subbulakshmi's ability to sculpt a soundscape that subconsciously became part of our collective memory.

Gowri Ramnarayan learnt from her that music should eschew excess regardless of the musician's particular gifts, which must be underplayed. She gave a detailed account of MS's role in the Tamil Isai movement.

Sangita Kalanidhi R Vedavalli who called her the polestar of Carnatic music, described her preferred kalapramanam as well-toned madhya laya. Revelling in the major ragas led by her favourite Sankarabharanam, MS did not favour vivadi ragas with the possible exception of Varali, Vedavalli said, while praising the viruttams MS sang before songs like O Rangasayee, or the Kamalamba navavaranam Dakshinamurte.

The late Thangam Ananthanarayanan, a relative, had once recalled how MS's mastery of briga and alukkal sangatis impressed Hindustani vocalist Siddheswari Devi with whom she repeated each phrase 108 times every morning during akara sadhakam in a variety of ragas.

Manohar Parnerkar reminded us that it was also the centenary year of another female icon, Shanta Apte, who appeared with Subbulakshmi in the film Savitri, and did not know a word of Tamil, but in true MS style, learnt the language "assiduously and enthusiastically" to be able to render both dialogue and songs in the film. Apte was a liberated woman in the Germaine Greer mould, he said, almost antithetical to MS, but both had several things in common, both smashed the gender barrier, and both sang in several languages, handling Rabindra Sangeet with elan, for instance, "as if to the manner born."

Musician and innovator Ramesh Vinayakam applauded her perfect kalapramanam among other things. "She maintained the same pace, right from the start of the pallavi through the niraval, through the kalpanaswaras until the very end." He was citing her rendering of Pakkala nilabadi in Kharaharapriya in a Music Academy concert.

Vocalist Vijay Siva recalled a rare instance of outrage on MS's part, when she let loose a shower of invective against Osama Bin Laden while speaking to a foreign visitor. While listing her numerous musical attributes, he stressed how she demonstrated the importance of full throated vocalisation from the diaphragm.

"Can we emulate her in generosity?" asked Sruti's US correspondent Shankar Ramachandran, who proposed that rasikas at MS centenary concerts be asked to donate to some of her favourite charities.

Music lover S.M. Sivakumar related the story of a concert in Ernakulam he had helped organise as a sabha secretary in 1976. MS was of course reputed for the many charities she supported in a big way through her concerts, but the proceeds of this concert went to discharge the debts of the family of a young musician who had played the tambura for MS.

To add a personal touch to this tribute, I had the good fortune of listening to her up close, at home--both hers and ours-- many times. The occasions when she and her guru Semmangudi Srinivasier sang together impromptu or more formally during a wedding for a small family audience were unforgettable. We all know that the tape of one such "jamming" session at KR Sundaram Iyer's residence was remastered years later with violin (RK Shriramkumar) and mridangam (KV Prasad) added and made available commercially. "Divine Unison", the result of that collaboration is a collector's favourite today.

MS also sang in the company of family members--daughters Radha Viswanathan and Vijaya Rajendran, Anandhi Ramachandran, Gowri Ramnarayan and others, and these were very special experiences for whoever happened to be around. Of course, there was nothing casual about any of these song sessions. They were always in perfect sruti and rhythm, with the tambura drone virtually mesmerising the listeners. Whether it was a brief song at a cradle ceremony or the swing ritual at a wedding, the MS stamp was never missing. It had class writ large over it. One of the most memorable oonjal songs by MS has been a composition of Pillai Perumal Iyengar, which was first rendered at the wedding of Vijaya and Kalki Rajendran's daughter. Tuned by Kadaiyanallur Venkatraman, the song was unfurled after rehearsals by the many women from the family who participated. The song was recorded by MS and Radha for All India Radio as well, and is available on youtube and the portal msstribute.org as well.

A personal favourite among all these informal singing sessions was when MS walked up over a rough flight of stairs yet unguarded by a banister, stood by a temporary alcove with pictures of gods and goddesses in a still unplastered house, and sang a few songs in an act of blessing for the griha pravesam ceremony in late 1992. I had lost my father a couple of months earlier, and the sheer beauty and power of her singing brought me memories of him in a flood of emotion. It was a moment of sublimation.